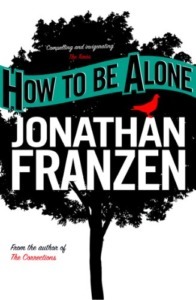

The other day, I was combing through my bookshelves for something new to read – we are all doing this at the moment, right? — when I came upon Jonathan Franzen’s book of essays entitled How To Be Alone. Somewhat nervously, I removed it from the shelf; I believe the term “on-the-nose” was coined for such moments.

we are all doing this at the moment, right? — when I came upon Jonathan Franzen’s book of essays entitled How To Be Alone. Somewhat nervously, I removed it from the shelf; I believe the term “on-the-nose” was coined for such moments.

But with all due respect to Franzen, whose book is witty and wistful and quite wonderful, my artistic guide to surviving this extraordinary, bewildering moment is not him, but Ludwig van Beethoven, who raised aloneness to the highest of art forms.

Recently, I played Beethoven’s wondrous last three piano sonatas in my living room, to an iPhone sitting on a thirteen dollar tripod. Just as urgent necessity has led to the creation of makeshift hospitals, this was a makeshift concert hall: the 92nd Street Y, where I was to have played the concert, is closed, as is nearly every music venue around the world. I won’t lie: I desperately miss the act of sharing this music with a live audience, and I’m filled with anxiety at not knowing when doing so will again be possible. A further truth: for as long as I’m not performing, I have no source of income, a situation which is frightening for me, and catastrophic for the thousands, if not millions, of freelance musicians everywhere.

But while the present moment is obviously deeply precarious and imperfect for art and artists, I can honestly say that I have never felt more purely connected to those staggering works than I did yesterday, playing them in total isolation. Because what artist has ever been more isolated than Beethoven? The deafness which plagued him for most of his adult life had, by the 1820s, left him entirely sequestered from the outside world. This tragedy, however unspeakable, had the effect of turning his already extraordinary imagination kaleidoscopic, his already enormous idealism infinite. Now that I am living a sequestered life myself, I feel the weight of his circumstances, and the miraculousness of what he achieved in spite of them, that much more keenly. In these dark days, it is one hell of a silver lining.

Jonathan Biss’ article was originally commissioned and first appeared in The Times.

Follow Jonathan Biss on Facebook for his daily Beethoven Sonata movements here

Watch Jonathan Biss’ Carnegie Hall masterclasses here

Main photos: Benjamin Ealovega