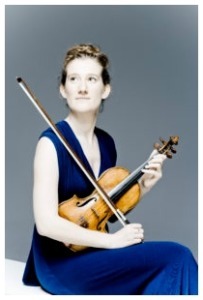

Maria Milstein’s recent CD, The Vinteuil Sonata, recorded with her pianist sister Nathalia and made possible through her BBT Fellowship 2016, also inspired her piece for The Arts Desk website, reprinted here with permission.

I rem ember very well the first time I read Swann’s Way, the first part of Marcel Proust’s monumental masterpiece, In Search of Lost Time (À la recherche du temps perdu). I was struck not only by the depth and beauty of the novel, but also the crucial role that music played in the narrative. For those who haven’t read the novel, here is a brief summary of the part that particularly fascinated me, “Swann’s Love.”

ember very well the first time I read Swann’s Way, the first part of Marcel Proust’s monumental masterpiece, In Search of Lost Time (À la recherche du temps perdu). I was struck not only by the depth and beauty of the novel, but also the crucial role that music played in the narrative. For those who haven’t read the novel, here is a brief summary of the part that particularly fascinated me, “Swann’s Love.”

Swann, one of the main characters in the novel, is a rich young man living in Paris who is connected with the highest Parisian aristocracy. At a musical soirée one evening he hears a sonata played by the invited pianist and suddenly recognises the music as the mysterious sonata for violin and piano that he had first heard some time ago and which had made a strong impression on him then. Hearing this music again makes him realise exactly what it was that fascinated him – a petite phrase (‘little phrase’) that appeared in the slow movement and returned later in the last movement. He discovers during the course of the evening that this piece was recently written by a composer named Vinteuil. Swann’s obsession with the sonata grows and he starts to identify the ‘little phrase’ with his love for Odette de Crécy, whom he meets at the same salon. As the love between Swann and Odette develops, flourishes and then diminishes, Swann is left with a broken heart and the sonata whose petite phrase keeps haunting him, appearing every time in a different light as his feelings develop and metamorphose.

The way Proust describes the Vinteuil Sonata is absolute genius, and is proof of the vast knowledge he had about music. One can almost hear the piece he is describing and many features, such as the cyclical form of the piece (the ‘little phrase’ returns in different movements of the sonata), the texture of the piano-writing and the moods the different sections convey, make one think that the Vinteuil Sonata is based on a prototype that really exists.

Since the publication of Swann’s Way in 1913 there have been numerous speculations about the possible model for the Vinteuil Sonata. Proust was a fervent music-lover who, partly through his relationship with the composer Reynaldo Hahn and partly through the cultural circles in which he moved, was introduced to the broad musical spectrum of turn-of-the-century Paris salons. Proust’s musical taste was cosmopolitan; he was a great admirer of Beethoven and Wagner, but also very interested in his contemporaries, such as Franck, Fauré and Debussy. When analysing the descriptions of the Vinteuil Sonata one can actually identify several possible candidates, including the violin sonatas of Franck, Fauré and Lekeu, which are often mentioned as plausible models.

In one of his letters, however, Proust does say that the inspiration for the description of la petite phrase was a “charming but mediocre theme from a sonata of Saint-Saëns”. Camille Saint-Saëns‘ First Violin Sonata, written several years before the completion of the novel, does indeed feature a second theme in the first movement (whose candour and apparent naivety perhaps made Proust consider it mediocre) which not only seems to correspond to the description of the “little phrase”, but also returns as the apotheosis of the last movement.

The Saint-Saëns Sonata was therefore my departure point for this rather ambitious project of recording an album inspired by the Vinteuil Sonata and the mystery surrounding it. My wish was not to unite in one recording all the possible prototypes – that would far exceed the length of a disc – but rather to recreate the atmosphere of a musical salon, such as Proust might have attended.

In our search for suitable repertoire my sister and I discovered the Violin Sonata Op 36 by Gabriel Pierné, then totally unknown to us. Pierné, a turn-of-the-century composer, was also a renowned conductor who premiered and championed many works of his more famous contemporaries, among whom was his close friend Claude Debussy. Pierné’s Violin Sonata, very impressionistic in its writing and rather demanding – as much for the pianist as for the violinist – amazed us with the freshness and variety of its melodies and the harmonic beauty underlying these fluid melodic lines. For us the dreamy second movement was a special coup de coeur. And the second theme from the first movement of this sonata also returns in the finale. We immediately felt that this unfairly forgotten piece had to feature in our project.

Immersing  myself deeper into the atmosphere of the novel with its broad and versatile use of associations, memories and flashbacks, I realised more and more that the musical counterpart of Proust, who changed the path of literature, would be Claude Debussy, who changed the path of classical music just as drastically. A contemporary of Proust, whose music was most probably known to the writer, Debussy composed his Violin Sonata just a few years after the publication of Swann’s Way in 1917. This sonata, with its mysterious opening (which returns as a flashback at the beginning of the last movement), awakens in the listener a whole world of associations; sometimes one can taste a flavour of Spain, sometimes one hears the sea, especially in the tempestuous last movement. For me, the introspective and sometimes dream-like quality of the music made a very logical link with Proust’s novel and the Vinteuil Sonata with its elusive ‘little phrase.’

myself deeper into the atmosphere of the novel with its broad and versatile use of associations, memories and flashbacks, I realised more and more that the musical counterpart of Proust, who changed the path of literature, would be Claude Debussy, who changed the path of classical music just as drastically. A contemporary of Proust, whose music was most probably known to the writer, Debussy composed his Violin Sonata just a few years after the publication of Swann’s Way in 1917. This sonata, with its mysterious opening (which returns as a flashback at the beginning of the last movement), awakens in the listener a whole world of associations; sometimes one can taste a flavour of Spain, sometimes one hears the sea, especially in the tempestuous last movement. For me, the introspective and sometimes dream-like quality of the music made a very logical link with Proust’s novel and the Vinteuil Sonata with its elusive ‘little phrase.’

To make the album complete we had to include works by Reynaldo Hahn, the lover and close friend of Proust, who played a significant role in the writer’s growing passion for music. Instead of choosing a piece for violin and piano I decided to turn to Hahn’s songs, some of which are true gems and probably among his most beloved works. À Chloris is a neo-baroque song in which the unnamed narrator sings of his love to Chloris; the allusion to Bach and his contemporaries suspends this song in time, the craving for a past long gone transcending the piece. L’Heure Exquise, based on a poem by Paul Verlaine, invites the listener to forget the passing of time and fully enjoy the exquisite moment; Rêvons, c’est l’heure (“Let’s dream, it is time”) could also be an appropriate title for our album. Making the choice to arrange these songs for violin and piano – thereby leaving the texts aside – was very conscious, not only because both songs work wonderfully on the violin, but also because the lack of text creates a sense of mystery, leaving one to guess what the song could be about.

The mystery around the Vinteuil Sonata remains unsolved and every reader should be able to hear his or her ‘own’ Vinteuil Sonata. This album, rather than dictating an answer, is merely suggesting a possible approach, and will hopefully prompt the listeners who haven’t yet read Proust’s masterpiece to plunge into the great novel In Search of Lost Time.

Photos: Marco Borggreve

Read the original The Arts Desk article here: